You Don't Have to Migrate to Python 3

You can put your pitchforks and torches down - Python 3 is great! If you can migrate your project from Python 2 to Python 3, then by all means, you should do this. But with all the praise of Python 3 and all the great talks on how to migrate, we are forgetting about a huge portion of Python 2 applications. Applications that can't be migrated. Or don't have to be migrated. So let's talk about those.

This article is based on a talk that I gave at PyCon Japan 2019 called "It's 2019 and I'm still using Python 2. Should I be worried?". If you prefer to watch the video instead of reading, you can click the link above.

Python 2 End of Life

Python 3 has been out for over 10 years. The initial EOL (End of Life) for Python 2 was set to 2015, but it was extended until 01.01.2020. Back in 2013 and 2014, people were not ready to move to Python 3. Python 3.0 was pretty much unusable, Python 3.1 and 3.2 were slower than Python 2. But the main problem was that many of the 3rd party libraries were still using Python 2. It wasn't until 2012 that half of the 200 most popular Python packages were migrated to Python 3 (based on the information from the "Python 3 Wall of Shame/Superpowers" website that is no longer working). And by 2018 still, only around 95% of those packages were migrated. And those are the most popular packages! For the more obscure ones, the statistics were probably even worse. So developers were not ready in 2015. Thus, the deadline got extended by another 5 years. During those 5 years, a lot has changed. The latest versions of Python 3 (3.6 and up) are amazing - fast, feature-rich (whether you like the walrus operator or not 😉), and simply a pleasure to work with. Most of the Python packages have been migrated to Python 3. And those that didn't, probably won't. So how come that in 2019 there are still projects that are using Python 2? Well, there are a few reasons that I can think of.

Why do we still have Python 2 projects?

The cost of migration is too high from a business point of view. As developers, we understand that for the past few years, every line of Python 2 code that we write is a technical debt. But most companies are not run by developers. We all have managers that make decisions based on what business value each project brings to the company. And the fact that a programming language will be obsolete in a few months is often not a good enough reason to spend time rewriting everything. Migrating from Python 2 to Python 3 is expensive. And quite often it feels like it won't bring any money to the company. It won't add new features to your product and, while it will bring some speed improvements to your project, if it was the raw speed that you were looking for, you probably wouldn't choose Python in the first place. I have never seen a product that has "Python 3" as one of its features on the landing page. Unless it's a product for developers.

There is always a new feature waiting in the pipeline or an urgent fix that needs to be deployed. And if you are "Agile" (because now everyone is "Agile") and you have a huge backlog, migrating to Python 3 is probably somewhere at the bottom of it. If it was lucky enough to even get into the backlog. If you are a small startup, you need to focus on adding new features and improving users' experience, not on writing the perfect, most up-to-date code. You don't have time for refactoring or rewriting code that just works.

And if you are not a small startup, but a big corporation, you have another problem. A large code base of legacy Python (and by large I mean, for example, 35 000 000 lines of Python 2 code). And migrating old code can be scary. Imagine you have some code written by a developer who left the company a long time ago. There are little or no tests and the documentation is very poor, often outdated (if there is any). The code works, so it's fine. But no one has any idea how it works. So no one has been touching it for years. It's a scary thought that at some point, you will have to rewrite it. So the code stays in Python 2.

Migration to a new version of a programming language is a similar problem to refactoring. In both cases you need to set aside some time to rewrite existing code, hoping that you will make it better in the long run. But refactoring can be done following a "boy scout" rule, that says "you should always leave the place in a better shape than how you found it". So when you are adding a feature to a function, you clean up that function a bit. Migration can't be done like that. Even though you can start writing straddling code (code that will work with both Python 2 and Python 3), you will still have to rewrite other parts of the application at some point.

Risks of staying on Python 2

Let's fast forward 2 months. Python 2 is officially dead, everyone is getting ready for the party to celebrate at PyCon 2020 and you are just sitting there with your production code still running on Python 2. And thinking: "What's the worst that can happen?"

You can get hacked. Well, you can get hacked on Python 3 or any other programming language, but on Python 2 there is a bigger chance of that. Python 2 will not get any updates and this also includes bug fixes. If there is a 0-day for Python 2 discovered on the 2nd of January - good luck and have fun fixing it. No one from the core developers is going to fix it. But it's not the Python interpreter itself that you should be worried about. Your main problem is probably going to be the packages that you are using. Most of them have already abandoned their Python 2 versions and many more will follow in January. The more dependencies you are using, the more likely some of them will have security issues.

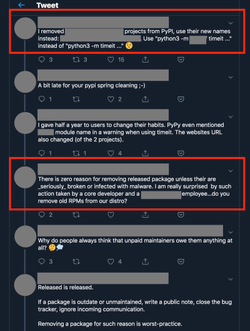

Even if there won't be any security issues with your software, as time goes, it will slowly start falling apart. Each time you update part of your system (and you will update them to stay secure), there is a chance that some of the underlying dependencies won't be happy with the new software. And maybe some developers will remove their packages from PyPI, tired of seeing users opening new issues in a project that they decided to deprecated a long time ago. In the end, you will spend more and more time firefighting to keep your project alive.

What can you do about Python 2 EOL?

So what can you do about the Python 2 End of Life? If you can migrate to Python 3, then do this! Long-term benefits will outweigh the cost of migration. But if you could migrate, you probably would do this long time ago and you wouldn't be reading this article. So I assume that you are looking for other solutions. Here is a list of solutions for Python 2 project, sorted by (my arbitrary feeling of) how difficult it is to implement each of them:

Do nothing

You can pretend that Python 3 never happened and ignore the whole Python 2 EOL problem. As I already mentioned before, by not updating your software you are risking that security vulnerabilities will sneak in (and sneak out your customers' data). Also, some of your dependencies might stop working at some point. But, if the only place where you use Python 2 is some kind of internal script that you run on your computer and it has no dependencies, then nothing is a perfectly fine thing to do! Don't update to Python 3 just because everyone tells you to do this (even though migrating such a simple script would be rather fast and easy). The same if you are expecting that your software will become obsolete next year (maybe you are working on another version already). Weigh the pros and cons of the migration and decide for yourself.

Freeze the state of your application

This is an interesting solution for all sorts of internal tools where you are not concerned about the security (by "internal" I mean - disconnected from the internet), but if some of the dependencies fail, you will be in trouble. Dependencies for Python 2 projects will start breaking next year. People will remove their old projects from GitHub or even PyPI, as I showed you above. Remember when we all laughed at JavaScript when someone removed a library that pads text left and suddenly all the builds started crashing? Well, prepare for that, but this time no one will really care, since "you are using a deprecated version of Python".

Luckily, we have docker! Or any other tool that lets you create immutable containers. Write a Dockerfile that uses Python 2 as a base image. Add all your dependencies there and set up your app as a docker image. Push that image to a public or private repository. And voilà, you have an immutable container with a working application! You can share it, reuse and you don't have to worry that some dependencies are no longer available. It solves most problems for internal tools. And you might want to do this now, not in 2020 when your application will already start giving you trouble.

Change Python interpreter

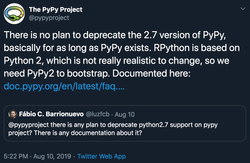

When I write "Python 2 EOL", I mean "CPython 2". CPython is the most popular Python interpreter, so for many people, Python == CPython. But it's not the only interpreter that we have. There is also, for example, PyPy which is a solid alternative to CPython. And since it's actually built on top of Python 2, PyPy is not planning to deprecate it at any point.

Don't think of PyPy as a "curiosity" that no one is using. PyPy is very mature, it's passing the same test suite as CPython (or as someone once joked "it's bug-to-bug compliant with CPython") and there are companies that have been using it in production for years. So it's a valid replacement for CPython 2. If you search on YouTube, you can find some examples of people happily running it in production - here is one.

So why isn't everyone using PyPy? Because it has some limitations. If your project relies heavily on C extensions, then PyPy might not be a good solution for you. But if you switch to PyPy and everything works fine - which you need to verify with tests - then your app might even run faster than before. Which is a nice side effect to have!

PyPy is not your only alternative. Intel is also maintaining its own distribution of Python called "Intel® Distribution for Python”. It's a free distribution that supports versions 2.7 and 3.6 of Python. When I spoke with one of the people involved in this project they assured me that they are also not planning to deprecate version 2.7 any time soon.

Commercial Python distributions

Finally, there are commercial solutions. One of them is Red Hat Enterprise Linux (RHEL). If you buy version 8, Red Hat will provide you with support for Python 2 until June 2024, as they are ensuring on their website. That could buy you 4 more years of bug fixes and updates for Python 2 ... at the price of switching from a free and open-source programming language to actually paying someone to use their distribution of Python. There are also other commercial vendors (that you can find on the internet) who will offer you paid support for Python 2 versions.

Maintain your own CPython 2 build

If you don't want to pay anyone for fixing Python 2, you can do this yourself! All you need to do is: fork the CPython repository, wait for vulnerabilities to appear, patch them, compile your own CPython version and use this on your production servers. It's exactly as tedious as it sounds and it's probably not the best idea unless you clearly know what you are doing. You don't want to be the one who introduces vulnerabilities on your server!

Migrate to Python 3

If none of the above options works for you, then you might end up migrating to Python 3. There are 2 common ways how you can do this: with straddling code or by rewriting Python 2 code to Python 3.

Straddling code

Straddling code is a code that works with both Python 2 and 3 at the same time. It sounds like more work, as you need to support both major Python versions, but it makes the transition easier - there is no sudden switch from Python 2 to Python 3. You start by running your tests under Python 3 (of course, most of them will fail) and you keep rewriting parts of your application until it works under Python 2 and Python 3. Then you change the Python version in production and finally, you remove the Python 2 code. The biggest advantage of this approach is that you can do this in iterations. You migrate parts of your system and you can keep adding new features to your code at the same time, so your customers will be happy.

Rewriting Python 2 to Python 3

The other option is to rewrite parts of Python 2 code in Python 3. It requires less work, as you don't care about Python 2 anymore. The typical approach is to keep Python 2 version of your app in production and start working on Python 3 version in a separate git branch. You keep testing the new version and when it's ready, you pull the plug on Python 2 code and turn on the Python 3 version. Which is scary as there might be things that you didn't test and then rolling back to Python 2 is going to be painful.

Also, this approach means that you need to stop adding features to your app. Otherwise, you will be doing double work - you will need to add those features to both Python 2 and Python 3 versions of your app.

Rewrite your application

The final and most difficult solution is to rewrite your application from scratch in Python 3 or in any other programming language that you think will work the best. This requires the biggest amount of work and it only makes sense if Python 2 version was just a prototype. But it lets you completely redesign your project, so maybe it will actually work well for you?

Should I migrate or not?

As I said at the beginning if you can migrate to Python 3, do this. Python 3 is faster than Python 2. It has plenty of great features like asyncio, type hints, ordered dictionaries, f-strings or better Unicode support. Most of the packages that were planning to migrate already did it. And those that didn't, probably won't migrate anyway. And finally - you won't be using a programming language that is no longer supported by its creators!

If you want to learn more about how to prepare for the migration process, watch the last part of my talk where I give some ideas or read the Python 3 porting book - it's a great, concise and free guide on how to survive the migration. See you on the other side of Python!

Photo by Nick Fewings on Unsplash